Fifty years ago, protest shook the world. Young people rose against tradition and authority in places as different as Berlin and Beijing. Some of the most dramatic events, however, took place in the Americas. 1968 might be a long time ago, and many people who took part in the uprisings, who helped quell them or who just watched with sympathies for one or the other side are dead by now, and most others have changed markedly since then. One thing, however, has not changed: Mention the upheaval of the 1960s and you’ll spark a debate. Many countries – including the United States – still debate the times and fight to interpret their meaning. But where did that big summer of discontent come from? What happened during the uprisings, and how did they end? This article will try to answer these questions – mostly for the United States, but to a lesser extent (due to my lack of knowledge, not for a lack of historical drama) also for Latin America.

Protest in the Making

Why did so many people all over the world take to the streets in 1968? It seems especially amazing given that most countries had experienced a long period of solid economic growth since the end of World War II. But therein lay a problem as well. Economic progress freed many people from the most gripping concerns they had had before, but consumerism could only fulfill so many of their wishes. Just as well, elites in many countries had gotten used to the constant progress and factored it into their ever grander promises of even brighter days ahead. The actual improvements could not keep up with these promises. Many young people, however – most of which had not experienced or could not remember anymore the hardships of earlier times – demanded that these promises of progress be fulfilled and the hardships of the present remedied.

The hippies and other counter-cultural movements opposed American foreign wars which they saw as imperialist interventions negatively impacting both the lives of the people in the war zone and the American soldiers. Image: Card Flower Power from Twilight Struggle, ©GMT Games.

The precise reasons for the protest differed from country to country. The United States were a fertile ground for widespread protest in 1968 since many Americans had already gathered experience with activism in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The Free Speech Movement on college campuses and the hippie counter-culture had experimented with various forms of dissent from the early 1960s on. The single biggest catalyst, however, was the war in Vietnam. The protesters detested the war both for moral and personal reasons. It seemed wrong that a superpower waged war against a small, poor country for unconvincing reasons and with unclear goals while employing often hideous and brutal means. At the same time, young men feared they might get drafted and sent to Vietnam themselves, and every American soldier who returned home in a casket left more people behind who questioned for what he had died. The Tet Offensive in early 1968 did not shatter the American positions in Vietnam, but it smashed the confidence of the American public in winning the war.[1]

The Summer of Protest

The Tet Offensive did not only affect the men and women in the streets. President Lyndon B. Johnson maintained that Tet had not been an American failure, but he also declared that he would not seek reelection. This led to an open race for the Democratic nomination which exposed the internal conflicts of the party: Sitting Vice President Hubert Humphrey represented the orthodox stance and relied on the support of the party establishment as well as the labor unions. Senator Eugene McCarthy had positioned himself as the anti-war challenger even before Johnson had dropped out of the race, so he appealed to many of the activists and protesting students. Finally, Senator Robert F. Kennedy joined the race, capitalizing on the fame the Kennedy name still had five years after John F. Kennedy’s assassination – especially among Catholics, African-Americans, and other racial or ethnic minorities. The New Deal coalition which had won the presidency for the Democrats seven out of nine times since 1932 (only the immensely popular Eisenhower could beat them) broke into parts.

This rift would only come to be fully felt later. In the short term, two other events made a special impact and raised the temperature for a really hot summer of protest: Martin Luther King was shot by a white supremacist on April 4. Only two months later, on June 6, Robert F. Kennedy was murdered, too. The progressive forces in America had lost two of their most revered leaders. It seemed as only the forces of the establishment remained. In late August 1968, the Democratic Party held its national convention in Chicago to nominate the presidential candidate in this volatile political climate. Anti-war protesters flocked to the city from all over the country. They gathered in the parks and tried to march on the convention center, playing cat-and-mouse with the police tasked to keep the city quiet and prevent any kind of disturbance to the convention. Enraged protesters and a rather repressive police strategy did not mix well. While both sides engaged in violence, it was only a means to the end of favorable media coverage – for the protesters, to bring their cause to the public, for the police, to justify their hardline strategy as appropriate. The actual convention (that nominated Vice President Humphrey as the candidate) was completely overshadowed.

Chicago, Chicago in Strategy&Tactics 21, January 1970. The importance of media exposure in the riots is illustrated by showing the fights on a TV. “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow” refers to the folk explanation behind the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 – that said cow knocked over a lantern. Image ©Decision Games.

The Chicago convention riots were captured in a board game only two years after the events. Jim Dunnigan, the godfather of SPI wargames, had a liking for designing political conflict games as well (especially in his younger years). His Chicago, Chicago pits two players as protesters and police against each other. While the two sides clash in parks and streets (the latter being advantageous to the police, because they can pick off individual protesters there), their conflict is tightly limited – with both sides jockeying for victory points as provided by media exposure. Especially the police must be wary of escalating too much since they lose immediately if they accidentally kill a protester. Another special rule to capture the feeling of the conflict is the extremely high attrition of protesters (of whom presumably a lot go home during the conflict) which is balanced by their similarly high rate of reinforcements (representing new protesters joining the fight).

Law and Order

So far, we have only heard of the political Left, of protesters and the Democratic National Convention. What about the Right? The Republicans fielded Richard Nixon as their presidential candidate, reputed to be a tough conservative. Nixon ran on a platform of law and order at home and an “honorable peace” in Vietnam. He aimed to win the disenchanted Southern whites away from the Democratic Party. Nixon’s strategically most important coup, however – and the one that foretold his later administration style best – was in matters of foreign policy. The Johnson administration threw all their weight into bringing peace in Vietnam on the way – not only for the peace itself, but also as a boost to Humphrey’s election campaign. Nixon figured that his chances were best if the war in Vietnam showed no sign of ending. Therefore, he set up a back channel with the South Vietnamese government and urged them not to participate in a possible peace conference. Once he was elected, he promised, he’d give them better terms. The ploy worked. In fall, the potential peace in Vietnam broke into pieces just like the New Deal coalition had broken apart in summer. Nixon won a comfortable victory at the polls. Despite all its cultural leftist flair, 1968 was politically a clear victory of the Right. In the long run, the year and its cultural and political clashes inspired and vitalized the following generations on both the Left and the Right. 1968 keeps being debated and re-interpreted in America until today.

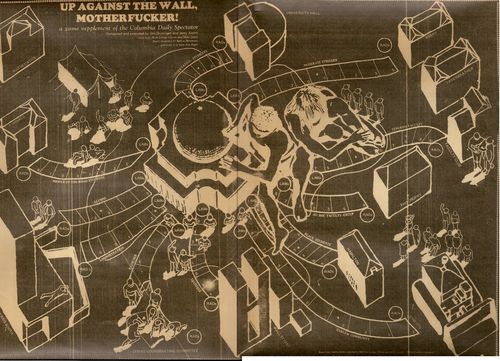

This polarization is also imminent in the board games covering the events. Another Jim Dunnigan game – one of his very first designs – that dealt with the protests at Columbia University proved controversial from the very beginning. I admit, it was not only because it featured a very recent political conflict very unlike the usual SPI fare of pushing tanks over the battlefields of World War II. It might also have helped that Dunnigan made some unconventional suggestion for the playing pieces in the rules – Seconal sleeping pills for the authorities, marijuana seeds for the radicals. But let’s face it, the single biggest reason for the game’s notoriety was its name: “Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker!”[2] SPI decided not to put a game with such a potential to offend into its Strategy & Tactics magazine. Just some subscribers were sent a free copy of the game to gauge interest (and level of offense taken). The game never made it to the magazine, but it could be purchased separately.

The – very fitting for the time of publication – slightly psychedelic map of Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker! The various tracks running towards the central library represent various student and societal groups.

Latin America: Protest in Authoritarian Regimes

1968 was a year of protest south of the Rio Grande as well. Most of the Latin American countries, however, were not exactly model democracies in the late 1960s, so protest was always a riskier business there.[3] My knowledge of Latin American history is regrettably limited, so I’ll just focus on two very prominent cases: Mexico and Uruguay.

Mexico had been ruled by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, “Institutional Revolutionary Party”) for almost forty years. Economically, the country had seen quite some success in the years leading up to 1968, and it was about to make history by being the first country of the Third World to host the Olympic Games (scheduled for October 1968). Growing prosperity and international prestige could not fulfil all desires, though. Especially the Olympics were often regarded as a mere publicity stunt that would do nothing to improve the situation of the populace. Instead the protesters demanded political change – especially more personal liberties: “¡No queremos olimpiadas, queremos revolución!” (“We don’t want Olympics, we want a revolution!” – an affront to a ruling party that had the claim to revolution in its very name). The International Olympic Committee, ever concerned with having undisturbed games, threatened to move the games to Los Angeles on short notice if the unrest kept growing. Under this kind of pressure (and heightened global attention), the Mexican government ordered tough measures to be taken against the protesters. On October 2 the police and the army surrounded the crowd of 10,000 gathered in the Tlatelolco neighborhood of Mexico City and opened fire. Hundreds were killed, thousands wounded or arrested. The Tlatelolco Massacre ended Mexico’s 1968 protests. Ten days later, the Olympics commenced as planned.

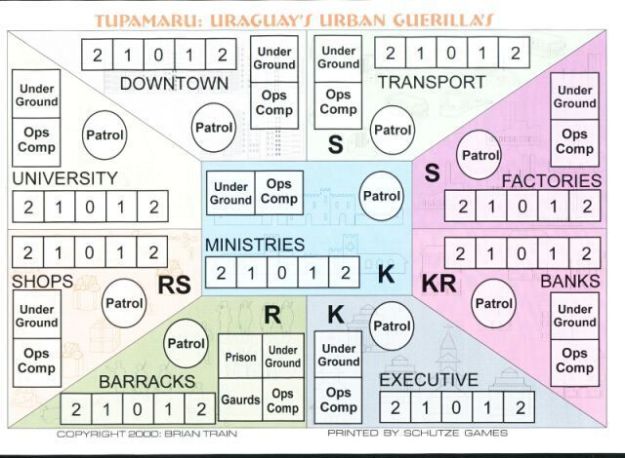

Uruguay’s case is rather special. The Uruguayan challenge to traditional authority did not come from spontaneous civilian discontent, but rather from an organized guerilla movement. The Tupamaro movement had been founded as a leftist political movement in the early 1960s already, adhering to a creed of “propaganda of action”. The more they clashed with the Uruguayan authorities, the more violent this action became. By June 1968, the Uruguayan president declared a state of emergency. Now the Tupamaros went underground and turned themselves into a fully-fledged urban guerilla group. They robbed banks to finance their fight and help the urban poor on whose support they depended, they orchestrated jailbreaks of their incarcerated comrades-in-arms, and they kidnapped or assassinated high-ranking Uruguayans and foreigners (including the consul of Brazil and a CIA agent who had been instructing the Uruguayan police about torture methods). This struggle of an urban guerilla group inspired many European left-wing radicals who subsequently shifted to armed violence as well (with not quite as much success), and also is behind Brian Train’s board game Tupamaro (BTR Games). The game is entirely de-territorialized – players do not fight to control ground, but social groups. They use their tongues as well as their fists to gain the allegiance of the populace and erode their opponent’s public support. Support, however, is not a zero-sum game – it is entirely possible that the populace becomes disenchanted with both sides and scores race towards the bottom. Whoever loses all their popular support also loses the game – as in real history, the Tupamaros faltered under their being rejected by the urban population as well as the heavy casualties and arrests among their fighters in 1972.

Tupamaro game board. As the game is deterritorialized, no area is contested – just segments of government, society, and economy.

The anti-war protest and urban guerilla movement did not remain confined to America. The next article of this series will deal with the 1968 protests in Western Europe.

Games Referenced

Twilight Struggle (Ananda Gupta/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)

Chicago, Chicago (Jim Dunnigan, SPI)

Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker! (Jim Dunnigan, Columbia Daily Spectator)

Tupamaro (Brian Train, BTR Games)

Further Reading

Mark Kurlansky gives a collage of the events, focused on how much they were globally inspiring each other via television in 1968: The Year that Rocked the World, Random House, New York City, NY 2005.

If you’re interested in how the idea of “change” lost to the idea of “law and order”, see Suri, Jeremi: Power and Protest. Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA/London 2003.

A short account of the ongoing debate over how to interpret 1968 in the US is Gitlin, Todd: USA: Unending 1968, in: German Historical Institute Bulletin Supplement, 6, 2009, online here.

Footnotes

1. This North Vietnamese success showed that the North Vietnamese understood the conflict and their enemy a lot better than the Americans did conversely, as Olivia Garard has shown here.

2. It has been speculated if this unabashedly graphic name was a snub at Avalon Hill, a company so concerned with their image as a producer of family-friendly fun that they changed the name of their racing game “Grand Prix” to “Le Mans” out of fear not-so-language-savvy shop assistants might mispronounce the French name.

3. If you’re interested in another article on protesting under authoritarian rule, see this one on the Eastern European Communist regimes in 1989 (heavily featuring the game 1989 (Ted Torgerson/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)).

Thanks for the mention of Tupamaro. One Small Step Games has recently come out with a folio edition of the game with new art and counters; it looks really nice.

As for the deterritorialized map, all of the action took place inside Montevideo, the capital city where more than half the population of the country lived (about 1.5 million people at the time, or about the size of Phoenix, Arizona).

Uruguay was trying to deal with a prolonged economic slump that had forced austerity on what had been a relatively generous distribution of wealth and jobs, the closest Latin America had come to a welfare state.

The conflict was as close to a pure war of class interests as one could get at the time – there were no ethnic, religious or linguistic schisms to exploit.

Therefore, both sides were fighting not for domination of a physical space but for the allegiance of certain social groups: discrete and kinetic actions took place within the city, over short and long periods of time, but the time-space-movement dilemmas faced by the designer of a conventional wargame didn’t matter.

So, I abandoned the whole idea of a map of the actual ground where the action took place.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Brian, thanks for reading and for your comment! I’m always interested in games that do things differently. It’s easy to do something the way others have done before, but that can also lead to transferring structures that don’t fit one’s own subject matter. Re-thinking and breaking genre conventions can often provide a thematically better solution – which I think the de-territorialized map of Tupamaro does very nicely, so I pointed it out specifically.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the vote of confidence!

Some players didn’t care for the idea at all, or for some of the mechanics – e.g. at the end of each turn player’s units, which during the turn had been deployed from a central abstract reserve (“Safe Zone” for the insurgents, Ready room or something like that for the government) to do operations, returned to base, as it were. They were clinging to the idea that police and troops, once deployed, could conquer and hang on to social attitudes as if they were physical territory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No game will suit all players – especially if they expected something different. And from a player perspective, new things are

1. Different from what they played and liked already

2. More things to learn before playing.

From a design/simulation aspect, however, it makes sense to go for new mechanisms for a new theme – and then you get a game about a political/urban guerilla struggle that feels like one. If it feels the same as a operational-level Eastern Front game, I assume the designer was not overly concerned with the simulation aspect. But I would not expect that to ever happen in a Brian Train game – especially when it deals with a political/sub-war violent struggle 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a truism that many gamers are quite conservative (in the psychological sense of the word, not the political, though there are those too). The slogan often seems to be, “give us more of the same, only different”. In my less charitable hours I think that many gamers play a game using the rules of the last game they played as far as they can make it work.

Most of the questions I get about my games I answer by pointing out the place in the rules where the question has already been answered. It makes me think that perhaps the Oral Tradition survives in teaching games, or that people don’t read at all. However, I recently read a thread on BGG where Charles Vasey made the same comment re his designs; he went on to say, though, that it wasn’t always as simple as people just not reading his rules. What he thought they were doing, without their making it plain, was that they were not agreeing with the rule, or the way the rule was written; in their own fractured way they were offering edits. I had never thought of it that way.

I’ve published around 50 games now, and have about another 6 or 7 about ready to go. I have a little chart that classifies them by “family” of design system: for example, the “4box” system includes Algeria, Andartes, EOKA, Kandahar and Shining Path. These are all different in several ways from each other, because the conflicts were not the same, but the underlying mechanism or armature is the same. I can classify about 30 of these this way, and another 25 or so use systems that I have used once only. Of course some systems borrow concepts from each other to some extent, which always happens, but then you make something new from them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting observation on gamers playing the current game by the rules of their last game! Quite like the British army was said to fight their wars 😉

And of course, re-using mechanisms is very useful – why not stick with something that has worked in the past? If the underlying theme is similar, that can free up design time and effort for other aspects.

Regarding the Oral Tradition: Yes, it is alive and kicking. For many gamers (myself included) learning rules is the least enjoyable part of gaming, so they try to get around it. As I tend to be host/game owner/explainer, I need to read the rule book, but many of my gaming friends rarely ever read rulebooks of games we play and rely on teaching by an experienced player (often me). There are limits to that when the games get more complex (e.g. our recent Here I Stand game).

“Edits phrased as rules questions” are an interesting interpretation. I think that often a sense of sheer disbelief that a rule would be in a way as it is written in the rulebook plays into that – possibly based on what people know from other games (“Everybody knows you cannot move out of a Zone of Control…”). Once more, thank you for your comments and your insights!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have had my share of incredulous questions and comments.

“Surely you don’t mean…?!?”

“Unerhoert!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post, Clio! And great comment stream too.

I think one other factor in missing rules (I know I have done this many times) is if a mechanic is similar to what we’ve seen before, we make an unconscious assumption about how it will work and our eyes just kind of gloss over the rule, even though the designer has tweaked the mechanism to fit the game.

Or sometimes we just don’t read closely enough, and since our understanding “makes sense,” we go with it even though it ends up being wrong.

I know I’ve done this often enough that any time I have a rules question, I say “I’m sure I’m just missing something, but I can’t find this. How do you…”

Because 90% of the time, I am missing something. The other 10%, it’s either not there or really ambiguous, but most of the time it’s the reader who’s at fault.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! And yes, any post gets instantly better when a designer like Brian Train comments on it 🙂

I think you’re on spot with your explanation for missing rules. When I teach games, I try to take people’s existing knowledge into account – so, when someone has experience with Twilight Struggle and I teach Wir sind das Volk! to them, I’ll say “You can play the card either for the event or for the operations points, but take care – unlike Twilight Struggle, when you play an opponent card for ops, the event does NOT trigger.”

And, of course, rules learning is not easy. I constantly have to look up something in the rulebook for the first five to ten times I play a game, and there’s no guarantee I wouldn’t miss the rule in question.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Magic May? (1968, #2) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Turmoil in the East: 1968 under Communism (1968, #3) | Clio's Board Games