As some of you know, I’ve been enrolled in university to complete my M.A. program in history for the last few years. It’s been the end of a long journey through academic history which began in 2010 with me as a bright-eyed freshman in my undergrad history classes. During these eight years, I have not only taken classes on everything from late classical Greece to the history of spaceflight. I’ve also interned, gone abroad for studying, worked for election campaigns, and finally taken up a regular day job before I’ve graduated. All of this has taken time, and that’s the reason why I spent a longer time enrolled in university than most. I even took longer for my M.A. than for my B.A. And all of this has given me valuable experience, made me more employable, and helped me grow as a person. I cordially recommend all of you out there who have the chance to look outside your college campus to seize this chance. The more you know outside of a classroom, the better for you, and for the world.

I know that not everybody has these opportunities. I was incredibly privileged. Personally, I’ve always enjoyed good health, and I had a generous student grant from a prestigious foundation to cover my living expenses. I was enrolled in programs that allowed for student engagement with the world off-campus, and I had advisers and supervisors who were flexible and encouraging about projects which might give experience but might also delay graduation. Most importantly, I come from a country where university does not cost more than a symbolic fee, and where students from low-income households even receive assistance in the form of half a grant, half an interest-free loan (of which no more than € 10,000 must be repaid). Without all these privileges, a young person like me – brought up in a single-parent, low-income household without any relatives who’d ever graduated from college when I enrolled – would have never been able to succeed like I did. I am grateful for that. I also regard it as a responsibility. I have been able to fulfil my potential because others and the society in which I live allowed me to. I will personally strive to enable others to fulfil their potential, and work for a society which allows as many people as possible to fulfil theirs.

This post, however, is not about my personal journey. As you know, this blog deals with history, board games, and history in board games. As it so happens, so did my M.A. thesis. I dealt with both my academic and my personal passion – the Cold War in board games. Let me share some insights of the thesis with you. If you’re interested in the why and how and what of the thesis, check out the research interest of the thesis, its methodology, and the sample of board games I used for it. You can also skip directly to my key findings on history-themed board games in general and the Cold War in board games in particular.

Why Should Historians Care About Board Games?

We live during a boom of history pop culture. History is a commercially successful force in forms as different as historical novels, renaissance fairs, re-enactment events – and board games. This boom of histotainment coincides with what has been called the Golden Age of Board Games. Unsurprisingly, there are thousands of games with a more-or-less historical theme (around half the BoardGameGeek Top 100 alone), and millions of people world-wide playing them.

Games, however, are different from other media as they give the consumers an active role and thereby allow them a stronger form of participation. And board games are different from electronic games as they must make the laws of the situation they model explicit, as the players have to understand the rules to implement them and successfully run a game. This makes history-themed board games fascinating purpose-built history worlds. My thesis aimed to

- Do theoretical and methodological groundwork for the historical analysis of board games and

- Gain insights on the depiction of the Cold War in board games based on thick evaluation of the sources

How Can Historians Analyze Board Games?

Only a few historians have ever researched board games, so I did not have a solid base from within my discipline upon which to build. I opted to adapt my theoretical and methodological framework from Game Studies, the discipline within the humanities dedicated to researching video games. Espen Aarseth, one of the leading Game Studies scholars, sees three dimensions of games:

- The structuring rules

- The materially-semiotic game world

- And the application of those rules on that game world: gameplay

To understand a game from a scientific perspective, a scholar must both play it and analyze it beyond play.[1] For the latter part, I had a deep look at the game components and the “paratexts” around the game – historical commentaries included with the game, designer’s notes, designer diaries, interviews… I also conducted interviews with the designers of all sampled games myself.

The Games in the Sample

The Cold War is not exactly the hottest historical theme for board games. Why deal with the embargo against Cuba if instead you can trade in the Mediterranean? Still, there are dozens of games linked to the Cold War. To limit my sample to a manageable size (and focus on the games that would be most informative and enlightening), I chose to analyze only games which

-

- Dealt with the Cold War in its entirety or multiple dimensions of it, no matter their spatial or temporal scope. I therefore left out games that only dealt with one dimension, most notably pure military conflict simulations, space race games, and espionage games set in the Cold War.

- Referred to specific events. I therefore left out games that used the Cold War purely for flavor.

- Were published commercially after 1989 (so that the Cold War was a matter of the past), but no later than 2016. The latter cutoff is of course arbitrary, but I had to draw the line somewhere, as more and more games were being published while I was working on the thesis.

In the end, my sample included the following six games:

Twilight Struggle (Ananda Gupta/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)

1989 (Ted Torgerson/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)

Wir sind das Volk! (Richard Sivél/Peer Sylvester, Histogame)

13 Days: The Cuban Missile Crisis (Asger Harding Granerud/Daniel Skjold Pedersen, Jolly Roger Games)

Twilight Squabble (David J. Mortimer, Alderac Entertainment Group)

Days of Ire: Budapest 1956 (Katalin Nimmerfroh/Dávid Turczi/Mihály Vincze, Cloud Island)

Key Findings on History-Themed Board Games

Board games turn their players into agents of history. They tend to assign a high degree of agency to the players which is mostly checked by the other players’ agency, not by other internal or external forces or contingencies. The focus of the games therefore lies on the subjects of history – the more powerful individuals and collectives, like rulers, strong states, efficiently organized groups – and not so much on the objects of their acts – the less fortunate people and communities.

Games have goals and usually produce winners. Therefore, history-themed games usually see history as a competition or confrontation.

As games are composed of theme and mechanisms, the individual game elements have a corresponding double nature: They need to be both authenticating and functional.

The Cold War in Board Games

Games about the Cold War fulfil this double nature in various ways. Visual design achieves this with the pervasive red-blue contrast in most games – red to denote pieces, events etc. of the East, blue for the West. The colors correspond with popular imagery and associations of the two sides. Another, less obvious example is the sub-division of event cards into multiple stacks which enter play in a programmed order. Mechanically, it allows for a certain control over events: Twilight Struggle players focus on Europe, Asia, and the Middle East during the Early War, as these are the only regions to be scored in that era and there are not a lot of cards that target other regions anyway. The authenticating flip side of this design choice is it creates a recognizable, close-to-history sequence of events – the Truman Doctrine is likely to happen before Nixon plays the China card.

Most games treat spatial control (or the denial of that to the opponent) as the key to victory. Spaces, however, are more than just their topography. They are primarily understood as their political, social, and economic capacities.

The Catholic church in the heart of Poland influences the five (!) adjacent worker spaces. Spatial and social relationships are strongly interwoven. Detail from the 1989 map, ©GMT Games.

The games feature an extremely strong bipolarity. Five of the six sampled games can only be played with two players, the sixth also allows for different player counts, but still keeps two sharply distinguished opposing sides (up to three players can play as a team in Days of Ire). Agents and events that do not correspond with this bipolarity (say, the Non-Aligned Movement or proponents of a “third way”) are usually either marginalized or forced into one camp or the other.

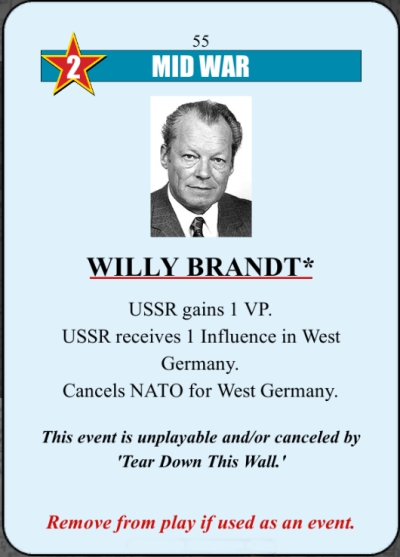

Willy Brandt conducted détente with the socialist East during his chancellorship – enough to make him a USSR card event in Twilight Struggle! Bipolarity leaves no space outside of the two camps in most games. Card “Willy Brandt” from Twilight Struggle, ©GMT Games.

States are dominant agents. Usually, the players identify with the superpowers (and sometimes their European allies). Only a few games even feature other playable powers (in the form of Eastern European dissidents). Agency also lies predominantly with states in the event cards.

These agents compete in various fields, but in none more than in politics. Mechanically, the Cold War is usually seen as a matter of realist power politics. Ideology, which was so defining for the actual Cold War, is almost exclusively evoked in theme (and usually also only for the Communist side, whereas the ideological assumptions and beliefs of the West are treated as a not-interesting-to-explore default). Especially games dedicated to longer historical timespans also feature competition in the field of technology (most prominently space and nuclear research, the great tech icons of the Cold War in public imagination) and the economy (which, surprisingly enough, is not so much understood as the material basis of state power and rather as the population’s sense of entitlement which governments need to pacify). Culture and day-to-day life are largely irrelevant to the games.

Finally, two distinct groups of Cold War-themed board games emerge, which I have called “global” and “European” games. Foreign policy dominates the “global” games. Nuclear weapons and the threat of nuclear war (after ideology the second defining characteristic of the Cold War) are important game features. The playable agents are without exception the superpowers which are treated as “black boxes” – equal in methods, capabilities, and victory conditions. In the “European” games, on the other hand, domestic politics are more important. European states and dissidents both have agency. The playable agents usually have asymmetric capabilities, and therefore also asymmetric victory conditions.

Games as a Bellwether of Popular Conceptions of the Cold War

Board games have shown themselves to be good indicators of which conceptions about the Cold War have made their way to a broader populace. They employ most prominently the narrative of the Cold War as a bipolar conflict of power politics which dominated scholarship especially during the 1970s and 1980s. Newer approaches to the Cold War – say, on the agency of smaller agents or the Cold War as a shared instead of a dividing experience in East and West – are barely reflected.

Board games are rich cultural artifacts which help to shape the ideas about history the players have. I cordially encourage my fellow historians to join in analyzing them.

Games Referenced

Twilight Struggle (Ananda Gupta/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)

1989 (Ted Torgerson/Jason Matthews, GMT Games)

Wir sind das Volk! (Richard Sivél/Peer Sylvester, Histogame)

13 Days: The Cuban Missile Crisis (Asger Harding Granerud/Daniel Skjold Pedersen, Jolly Roger Games)

Twilight Squabble (David J. Mortimer, Alderac Entertainment Group)

Days of Ire: Budapest 1956 (Katalin Nimmerfroh/Dávid Turczi/Mihály Vincze, Cloud Island)

Footnote

1. As research goes, playing board games is pretty good. A pity it made up only (roughly) 1-2% of the time I spent on the thesis.

Congratulations! . Is great to read your words about de wargames and research in history, I feel totally identified with them. Last year I finished an M.A. on military history based on wargames and military history.

https://www.academia.edu/34715471/La_simulaci%C3%B3n_hist%C3%B3rica_y_la_historia_militar

Is it possible to consult your thesis somewhere?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I had a look at your thesis: It looks very interesting! Sadly, I won’t be able to fully appreciate it as I don’t read Spanish. (My Portuguese and French were helpful enough to make sense of the table of contents, at least, and I saw some very nice pictures – Volko Ruhnke teaching officer candidates Fire in the Lake, for example).

Which brings me to my own thesis: It’s written in German, so I don’t know if that’d be of any use to you. As I am still weighing some publication options, I have not made it available online yet, but in case you read German and would be interested, let me know!

LikeLike

JAJAJA!!! . I read spanish, catalan, portuguese (my BA is portuguese), french , italian, but I do not know any German word, apart from “spiel” 😉 😉 Is it possible to have a list of the biography? sure there is some interesting reading in English;) . Thanks in advance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That footnote is to shut up smartasses like me, who were about to say it sounded pretty chill to play games as a thesis 😂

Great post. Nice to see the results of my suffering through Days of Ire’s downright stressful gameplay 😁

I am curious to know – what games are there that focus on the space race during the Cold War? -which, in my opinion, is a pretty hot topic?-

LikeLiked by 1 person

Naty, thank you for your contribution as one of my volunteers playing games with me! Even if I only remember our revolution being crushed by Soviet tanks. Sad!

Regarding the space race: Of the games in my thesis, Twilight Squabble and Twilight Struggle have important space race subsystems. So does Wir sind das Volk!, but only if you play with the expansion for four players that brings the superpowers in. There are a few games that only deal with the space race, importantly Space Race: The Card Game, and 1969. If you want more details, look no further than to your best source of education and entertainment pertaining to history, board games, and history in board games: https://cliosboardgames.wordpress.com/2017/10/06/sputnik-and-the-beginning-of-the-space-race/#boardgames.

LikeLike

Congratulations!

I hope you will enjoy the upcoming sequel to Days of Ire (we worked out some link rules to allow consecutive play of the two).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Brian! I’m curious about the link rules. Is there a document for them online?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure if they are online anywhere, but they come with the expansion kit, which you need for the link game.

It includes a set of 16 leader cards (named for the fighters in Days, most of which have a one-time effect but some persistent effects ones too) and 14 scenario cards (7 favouring the rebels, 7 favouring the Soviets).

These cards can be used independently of “Days”, to alter play balance and conditions for the sequel game “Nights”.

But you can play a campaign game by playing a game of Days, with 6 scenario cards (3 of each type) picked randomly at the beginning of the game.

During play some of the scenario cards will be triggered by in-game events, and will be in effect for the sequel game.

Also, any fighters left alive after the Days game become Leaders in the sequel game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations on the achievement! great job! theme and approach very interesting!😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Moka!

LikeLike

Pingback: SPIEL 2018: Most Anticipated | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Meeple Monthly Roundup, October 2018 – Meeple Like Us

As a general question, and apologies if you’ve dealt with this elsewhere, do you think that appropriate board games can help students learn history? At the very least by helping them to learn the places, people and events which were involved?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutly yes! 😉

https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departments/warstudies/people/professors/sabin/downloads/SIMULATIONTECHNIQUESINTHEMODELLINGOFPASTCONFLICTS.doc

https://warontherocks.com/2016/04/wargaming-in-the-classroom-an-odyssey/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think board games can be a useful addition to teaching/learning history. They motivate (some) students with their entertainment value as games, and they are good at showing factors in a decision-making process as well as having some potential for teaching causality, probability, and making judgments about history.

As you mentioned, they can also serve as “flash cards” to make students familiar with people, places, events – and, ideally, make them curious as to what happened so they will want to find out more.

The older students are (so, older high school or college students), the more they should also engage the game as an interpretation of history and untangle the game’s premises and conclusions. At my university, there have been various classes about movies with a historical topic (ranging from antiquity, as in Gladiator, to Cold War contemporary spy movies, like James Bond). I don’t see why there couldn’t be classes that use games as their sources of popular culture about history.

And, of course, thanks to gamesandco for the insightful links!

LikeLike

Pingback: Farewell 2018 – New-to-me Board Games | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Farewell 2018 – Highlights on the Blog | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Twilight Squabble (Games about the Cold War, #1) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Review – 13 Days: The Cuban Missile Crisis – Dude! Take Your Turn!

Pingback: Twilight Struggle (Games about the Cold War, #8) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Twilight Struggle’s Cold War Legacy | Inside GMT blog

Pingback: If you liked this book, try this board game! feat. @cliosboardgames | Naty's Bookshelf

Pingback: Farewell 2019 – On the Blog | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: What Was Decolonization? (Decolonization, #1) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Book Review: Do You Want Total War? (Darren Kilfara) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Farewell 2020 – The Best on the Blog | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Board Game Geek War Game Top 60: #30-21 | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Shelf Statistics, #1 | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: How I Became a Board Gamer | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Farewell 2022 – The Best on the Blog! | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: My Favorite Card: Decolonization (Twilight Struggle) | Clio's Board Games

Pingback: Farewell 2023 – Best on the Blog! | Clio's Board Games